With rising rates potentially on the horizon, protecting the value of bond portfolios is top of mind for many investors. Holding bonds to maturity via a bond ladder can be considered a way to navigate these volatile investing waters.

Why Ladder?

In a typical ladder, an investor would invest an equal amount of money into a series of bonds, with each bond maturing in a different year. When one bond matures, the proceeds can be used to purchase a new long maturity bond, or can be used for some other purpose. As each bond approaches maturity the duration, or interest rate sensitivity, of the bond portfolio declines. When a bond matures and a new longer maturity bond is purchased, the duration lengthens again. Investors effectively lock in yields on bonds when they purchase them, and take some of the guesswork out of bond investing. Also, a ladder gives an investor the flexibility of taking the proceeds from maturing bonds and using them for some other purpose.

Performance Comparison

How has building a bond ladder compared to investing in a short-term municipal bond strategy?

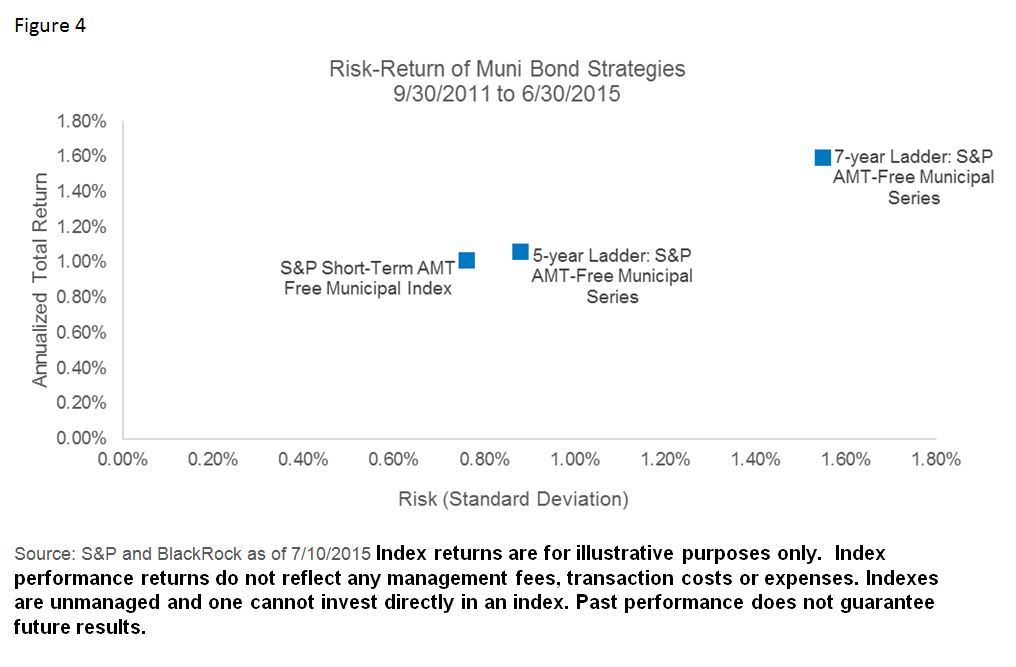

Let’s say an investor was considering three options: creating a five-year ladder, creating a seven-year ladder, or investing in a short-term municipal bond fund. For each of these investment options the investor is considering only non-callable, investment grade bonds. The performance of S&P AMT-Free Municipal indices can be used to measure how different segments of the muni market have performed over time; through them we can measure the historical performance of the three options. For our performance period we will look at September 2011 to June 2015. The S&P AMT-Free Municipal Series Indices include bonds that mature in each calendar year of the index name, and are available in maturities ranging from 2012 to 2023. A five-year ladder can be constructed using Municipal Series Indices that mature between 2012 and 2019. A seven-year ladder can be constructed using Municipal Series Indices that mature between 2012 and 2021. This analysis assumes that the investor is rolling the proceeds of each maturing index into a new longest rung on the ladder.

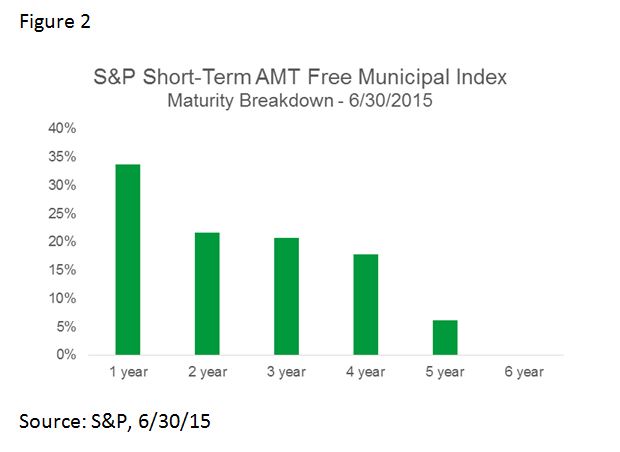

The performance of these ladder portfolios can be compared to the S&P Short-Term National AMT-Free Municipal Bond Index, which holds bonds from 0-5 years to maturity and rebalances monthly. The Short-Term index can be a good proxy for a short-term muni strategy that does not mature like a ladder. The index is market cap weighted, and does not hold an equal weighted amount in each maturity year like the laddered solutions do.

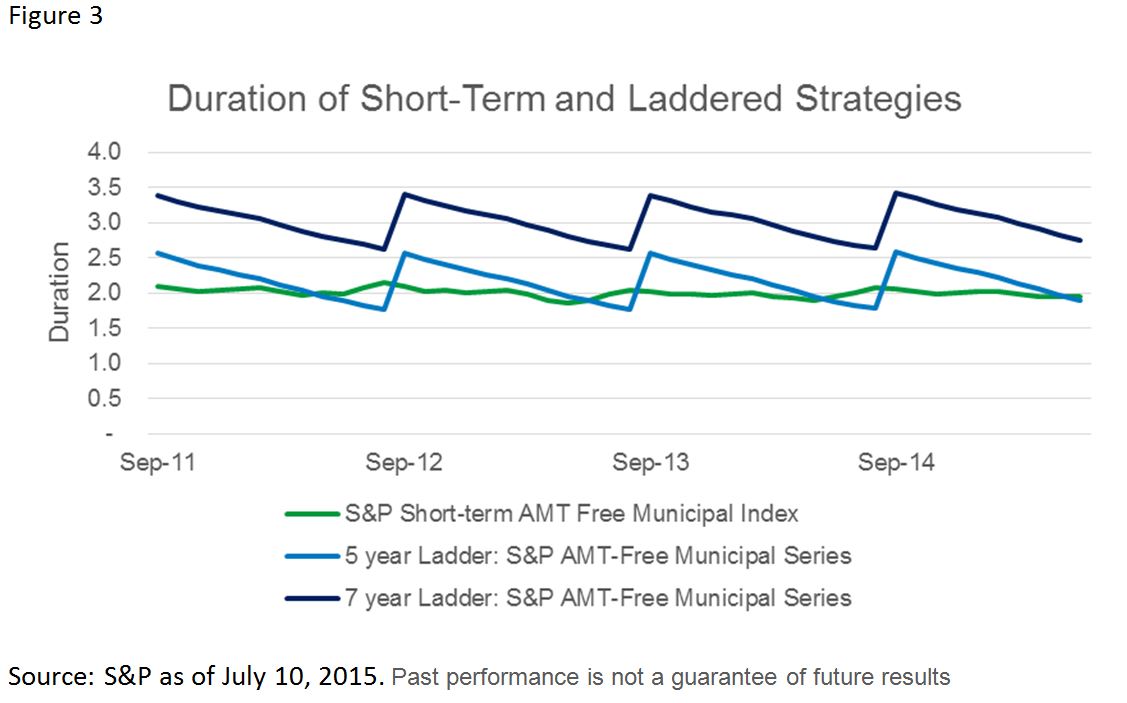

The duration of the laddered strategies rolls down and then increases when an index matures and the proceeds are reinvested in the next rung. This is in contrast to the Short-Term index whose duration is more stable through time.

The performance of the 5-year ladder and the short-term index were similar. Note that the 5-year ladder had slightly higher return and volatility due to having an average duration that was slightly higher. Overall the duration differences between the three different portfolios was the largest driver of their performance differences.

Laddering a bond portfolio can provide investors with the flexibility to navigate the next round of rate hikes, while still helping meet their investment objectives. A laddering strategy can also provide more control over the portfolio, as an investor has an opportunity each year to reduce the size of the investor’s bond investment. A short-term municipal bond strategy has provided a similar risk and return experience to the ladder options, and might be appropriate if the investor does not want to manage the maintenance of a ladder, or does not need the option of withdrawing proceeds from the investment on a regular basis.

—————————————————————————————————————-

The strategies discussed are strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and should not be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell, or an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. There is no guarantee that any strategies discussed will be effective.

Fixed income risks include interest-rate and credit risk. Typically, when interest rates rise, there is a corresponding decline in bond values. Credit risk refers to the possibility that the bond issuer will not be able to make principal and interest payments. There may be less information on the financial condition of municipal issuers than for public corporations. The market for municipal bonds may be less liquid than for taxable bonds. Some investors may be subject to federal or state income taxes or the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Capital gains distributions, if any, are taxable.

iSHARES and BLACKROCK are registered trademarks of BlackRock, Inc., or its subsidiaries. All other marks are the property of their respective owners. iS-16101-0715

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.