While the idea of reflation is picking up steam in global markets, Japan’s core consumer price index rose 0.2% in February 2017, which remained far below the target of 2% set by the Bank of Japan (BoJ). The BoJ kept monetary policy steady in March 2017, continuing the diverging policy paths of central banks.

In fact, despite the rising-rate environment in the U.S., the last BoJ minutes noted that “the monetary policy in Japan should be decided based on Japan’s economic activity and prices.” It also dropped hints by adding, “It will be a considerable amount of time before the Bank will need to change its monetary policy.” In an attempt to achieve the “price stability target” of 2% at the earliest possible time, the Bank of Japan introduced the quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) with yield curve control in September 2016.

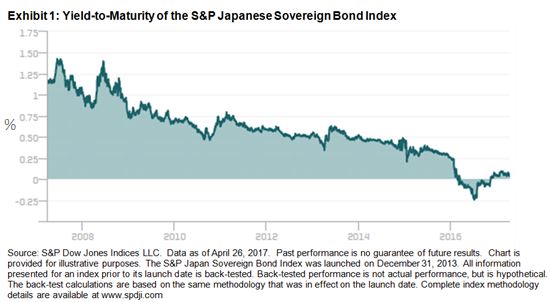

Japanese sovereign bonds, as tracked by the S&P Japanese Sovereign Bond Index, delivered a total return of -0.01% YTD and -1.79% for the one-year period as of April 26, 2017. Looking at a 10-year period, its yield-to-maturity tightened from 1.14% to 0.05%, after spending 9 months in negative territory last year (see Exhibit 1). The yield reached its lowest point (-0.25%) on July 8, 2016.

The S&P Japanese Sovereign Bond Index currently tracks 304 bonds with a total market value of 919 trillion yen, which is equivalent to USD 8.4 trillion. As of April 18, 2017, the government debt to GDP of Japan was at 250%, compared with 44% for China and 104% for the U.S.[1] All eyes will be on the next monetary policy meeting, which is scheduled for April 26 and 27, 2017.

[1] Source: Trading Economics. Data as of April 18, 2017.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

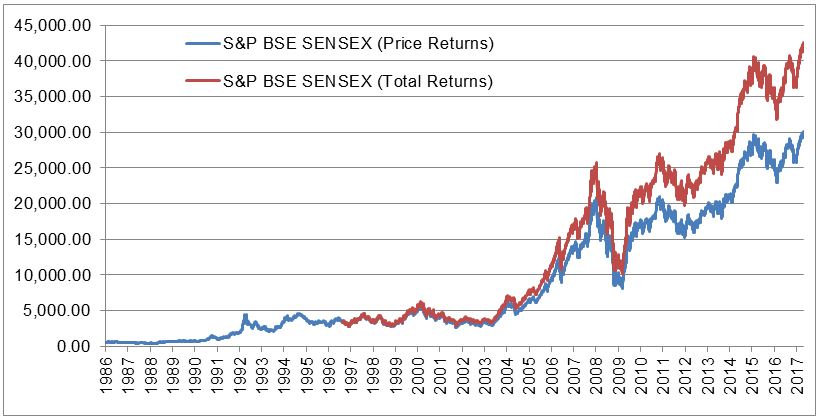

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Data from Jan. 2, 1986, to Apr. 26, 2017. Chart is provided for illustrative purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Data from Jan. 2, 1986, to Apr. 26, 2017. Chart is provided for illustrative purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.