This blog post was co-authored with Matthew Brown, President and COO, MSR Investments, LLC.

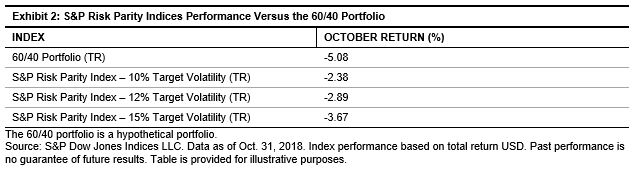

We believe there are two critical criteria an index must meet to be considered a benchmark: 1) it must be easy to implement as a viable investment alternative to managers that pursue the same strategy, and 2) it must define only the underlying beta that is common to the portfolios of all managers of the strategy. #1 is the reason we believe futures contracts work as constituents to the S&P Family of Risk Parity Indexes. #2 is the reason we approve credit as an excluded asset class in this family of benchmarks.

The fact that some practitioners of risk parity have chosen to exclude credit from their portfolios would be reason enough to exclude credit from a benchmark. However, we would like to take this opportunity to provide a more thorough explanation. When we analyze the returns of credit indices and their impact on relative performance inside a risk parity portfolio, it becomes clear that when an investor gains exposure to credit they may in fact be gaining exposure to 3 underlying betas: 1) equities, 2) fixed income, and 3) short volatility. Therefore, if we add credit exposure to a theoretical risk parity portfolio (or index) then we may simply be increasing exposure to equity and fixed income beta, which also ultimately has the effect of reducing exposure to commodities – the “parity” portion of the strategy is disrupted. Furthermore, to add credit to the benchmark may also accidentally add a new, undesirable beta to the strategy – short volatility.

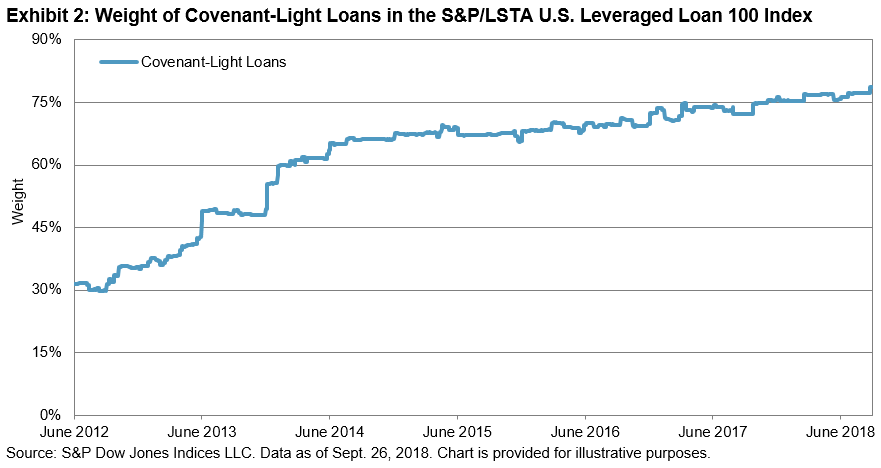

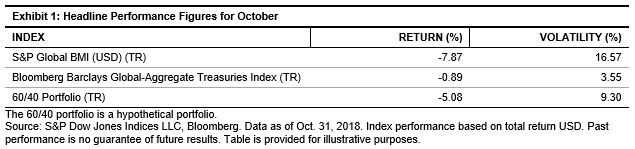

Since the end of 2008 to the end of September 2018, the daily serial correlation of the S&P 500 High Yield Corporate Bond Index is 0.46 along with 63.8% of positive return days. These are both extraordinarily high numbers and are often endemic to option selling strategies. [There is no explicit option selling in the index, so high yield investors are implicitly selling volatility.] This concept manifests itself in a conditional correlation relationship with equities where the correlation (between equities and high yield credit) rises towards 1 with spikes in market volatility. You need to look no further than the market behavior of February and October of this year to see an example of this phenomena.

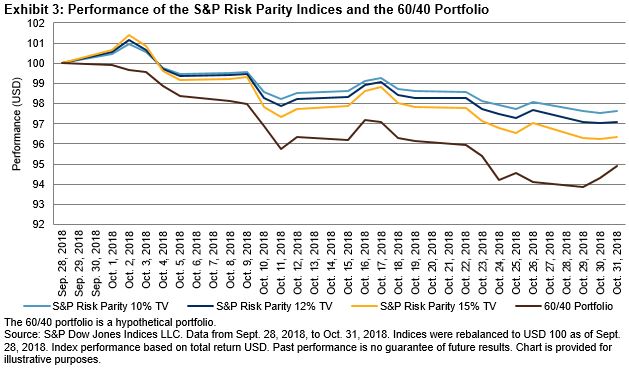

We also compared the relative performance of risk parity managers (using a popular 10% Target Volatility (“TV”) manager-based risk parity index as a proxy for manager returns) to the S&P TV10 Risk Parity Benchmark over time to a theoretical 50/50 (Equities/Fixed Income) TV10 portfolio of futures contracts. We correlated the relative performance of rolling 12 month returns of managers (i.e. managers’ return minus the benchmark return) to the 50/50 TV10 portfolio and got a correlation of 0.73 over the last eight years (prior to eight years ago there were very few managers in this space). This comparison demonstrates that by adding credit to their portfolios, managers may simply be adding equity and fixed income beta, which the S&P Benchmarks already capture. The two reasons that correlation isn’t even higher are likely 1) some managers (including the inventor of the strategy) do not invest in credit, and 2) the aforementioned exposure to volatility.

None of this analysis precludes the inclusion of credit in a risk parity portfolio. The reason to hire a manager is because you want that manager to provide alpha relative to the benchmark. We simply see credit as an alpha pursuing vehicle that combines underlying betas rather than providing exposure to its own unique beta. And we don’t believe any this information should be controversial because an investor has the choice to invest with a manager or invest in investment products linked to the benchmark. The manager vs benchmark analysis is now the same in risk parity as it is in other asset classes thanks to the S&P Family of Risk Parity Indexes.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source: