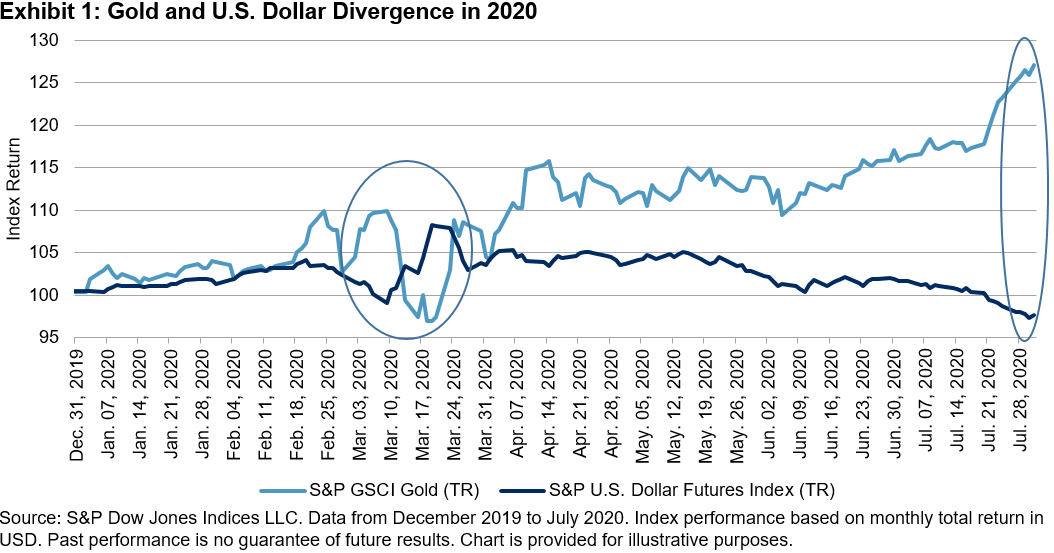

Despite the drop in volatility in many asset classes over the summer, some broke through key support and resistance levels.

The S&P GSCI Gold (TR) was one of them, reaching a new all-time high of USD 1,056.83 on Aug. 6, 2020, eclipsing the previous high from the summer of 2011. The underlying gold futures had reached new highs in several different major currencies over the past year, and they finally broke through in U.S. dollar terms.

Gold’s unprecedented rise is driven to a great extent by the bearish sentiment surrounding the U.S. dollar. Lower real rates and widespread fiscal and monetary stimulus measures have boosted demand for bullion, which is seen as a hedge against inflation and currency debasement. With many government bonds paying investors a negative return, the fact that gold is a financial asset that offers no income has become increasingly irrelevant.

Weakness in the U.S. dollar against a range of currencies is also supporting gold prices. The broad S&P U.S. Dollar Futures Index fell to a two-year low at the end of July 2020; in the eyes of some investors, gold is likely replacing the U.S. dollar as the ultimate safe currency. This break lower was a positive catalyst for gold to make new highs in the last week of July. Historically, there have been periods when the correlation between gold and the U.S. dollar was significantly negative. Current market conditions are ripe for the strength of negative correlation we are seeing in 2020 (see Exhibit 1).

Why is there such a strong negative correlation between gold and the U.S. dollar? The original use of gold was as a form of monetary exchange and store of value, just as the U.S. dollar is used today. The complementary nature of the two create an environment in which market participants tend to move from one to the other. When the U.S. dollar decreases, market participants look to other asset classes as alternative stores of value. Given that gold and most commodities are denominated in U.S. dollars, any depreciation in the dollar, by definition, increases the purchasing power of other currencies, potentially increasing the demand for commodities in those regions.

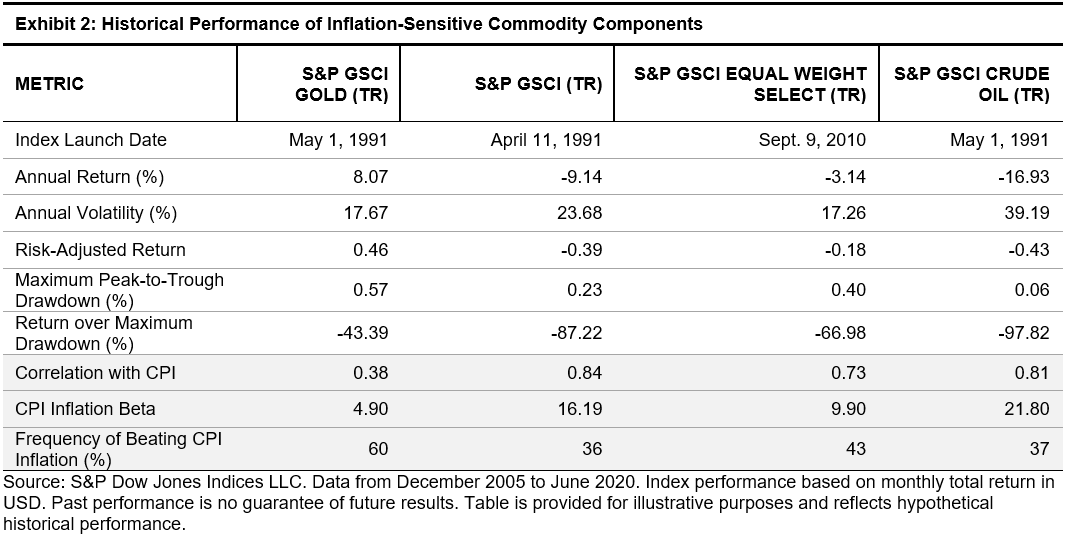

Faced with both an unprecedented shock and policy response, it remains unclear how inflationary the economic recovery will be, but inflation has certainly returned to the vocabulary of some investors. Gold is an inflation-sensitive asset. Inflation protection is a typical reason people look to commodities, and gold, to hedge their exposure. Over the long term, gold does not always move with inflation, but the two tend to be positively correlated (see Exhibit 2). Gold tends to be a better hedge than crude oil, especially during times of unexpected inflation. Over the past 40 years, the S&P GSCI Gold had a positively correlated performance to the U.S. CPI. Late business cycle environments tend to be a time for gold to shine—possibly more so than times of high inflation.

For more insight on gold, check out our previous blog that highlights why now is Gold’s Time to Shine. S&P DJI also released the first Spotlight on Commodities newsletter, containing relevant content for market participants looking to understand the performance of commodities this year.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.