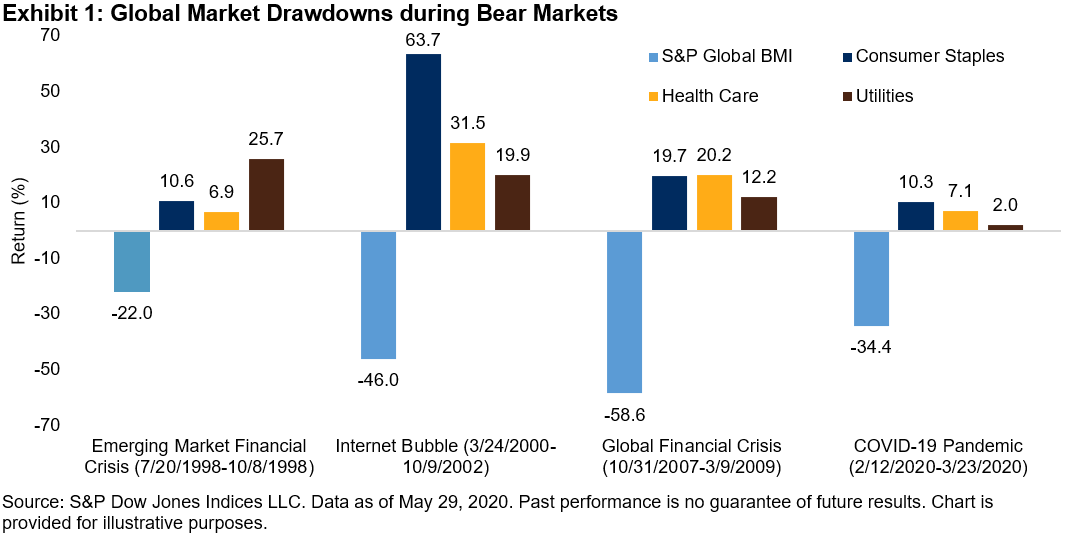

In March 2020, the S&P Global BMI TR declined 14.3%, marking its third-worst month over the past 25 years. Meanwhile, some sectors within the index recorded significant outperformances compared with the broader market. The S&P Global BMI Health Care, S&P Global BMI Consumer Staples, and S&P Global BMI Utilities surpassed the benchmark by 9.9%, 8.9%, and 2.4%, respectively.

Since Dec. 31, 1994, the global equity market has experienced four severe downturns when the S&P Global BMI TR declined 20% or more. However, three sectors—consumer staples, health care, and utilities—stayed in positive territory during all the drawdowns. Exhibit 1 shows how these sectors performed during the four worst drawdown periods. While the broader market suffered an average 40% loss, the gains from consumer staples, health care, and utilities sectors averaged 26%, 16%, and 15%, respectively.

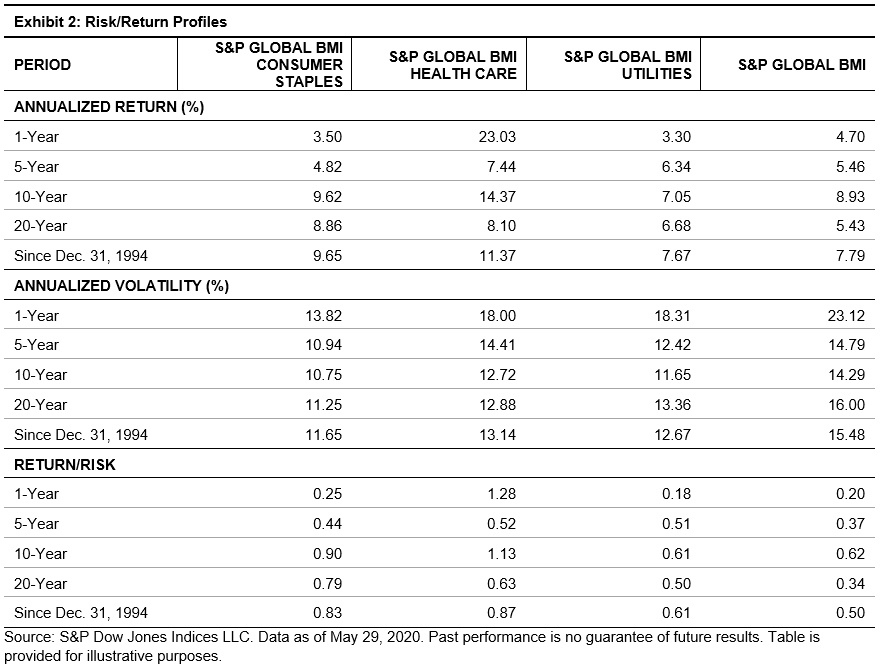

Over the long run, the consumer staples, health care, and utilities sectors generated the highest excess risk-adjusted returns. From the end of 1994 through May 29, 2020, the risk-adjusted returns from the consumer staples, health care, and utilities sectors were 0.83, 0.87, and 0.61, respectively, greatly exceeding the benchmark’s 0.50. In addition, as shown in Exhibit 2, the three sectors produced significant excess returns over almost all investment horizons. One year through 2020, consumer staples, health care, and utilities have delivered risk-adjusted returns of 0.0.25, 1.28, and 0.18, respectively, compared to the 0.20 generated by the benchmark.

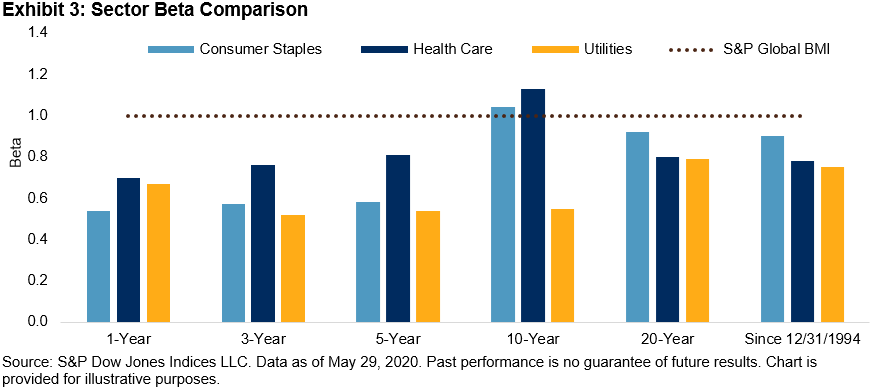

The underlying business models helped to make the consumer staples, health care, and utilities sectors less sensitive to economic cycles and more resistant to the market downturns. The consumer staples sector includes companies that provide goods and services such as food, beverages, and non-durable household products. The health care sector is composed of companies that provide medical and related products and services, and the utilities sector comprises companies that produce and deliver electricity, gas, or water to their customers. The products and services in these sectors are essential items that people need during all phases of the economic cycles, regardless of financial conditions. The stable demand can help these sectors generate steady revenues under various economic situations. As shown in Exhibit 3, the betas over various investment horizons indicate that these sectors were much less sensitive to the market.

The consumer staples, health care, and utilities sectors have had strong performance during the market slowdowns when observed over the short and long term. Understanding the sector characteristics, performance, and volatility profile can help investors decide on appropriate investments, participate in growth opportunities, and benefit during challenging times.