Through the end of July, equities had netted a nice gain for 2019 (though the picture looks a lot different so far in August). Unusually, the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index® outperformed in an environment when it has typically lagged its benchmark. (The S&P 500 gained 20.2%, while the low volatility index was up 20.8%, thru July 2019.)

Similar to its last quarterly rebalance, turnover in the low volatility index was limited, with changes taking place following the market close on August 16, 2019. Sector allocations are strikingly similar to the previous rebalance, with Financials, Technology and Utilities adjusting slightly higher while Consumer Discretionary, Health Care and Real Estate scaled back marginally.

The Latest Rebalance for the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index Yielded Minimal Changes

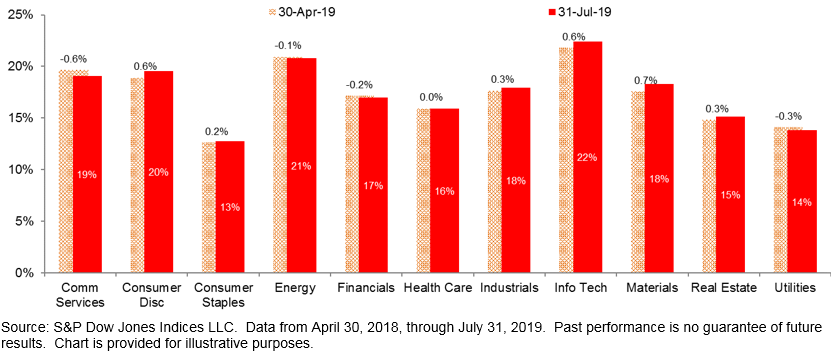

Trailing one-year volatility for S&P 500 sectors, a gauge we use sometimes use to gain insight, barely budged in the last three months. This is consistent across all 10 sectors. It’s therefore not surprising that turnover activity over the last two rebalances is at the lowest annualized level on record.

252-Day Volatility Changed Little Across All S&P 500 Sectors Compared to Three Months Ago