Investors typically flock to active funds to pass on the stock-picking decision making to a seasoned fund manager, with the hope that the fund manager’s experience and stock-picking capabilities will enable the investor’s portfolio to grow at a faster pace than that set by the benchmark. By using this approach, investors are able to circumvent one problem, only to get stuck in another problem: which fund manager to choose?

As seen in the SPIVA® India Year-End 2018 Scorecard, a large proportion of active fund managers underperformed the benchmark. Over the 10-year period observed, 64% of the large-cap funds underperformed the benchmark, the S&P BSE 100.

In the Indian Equity Large-Cap and Indian Mid-/Small-Cap categories, there was a wide spread in fund performance across different investment horizons (see Exhibit 1). For example, the spread in returns for an investor in two different large-cap funds over a 10-year horizon ending Dec. 31, 2018, could have been as high as 13.2% CAGR. Therefore, the selection of a fund can play a critical role in portfolio returns. The performance range in the case of the Mid-/Small-Cap category was even higher, at 14.92% over a 10-year horizon. The story remains the same across different time horizons. Furthermore, the average net returns generated by active funds were not far off from the benchmark returns (see Exhibit 1).

We also studied the distribution of fund returns and calculated their mean, standard deviation, and skew (see Exhibit 2). The study compared the fund returns data distribution with a hypothetical normal curve constructed with the same mean and standard deviation. Again, we considered the large-cap category and mid-/small-cap category for this analysis.

We also studied the distribution of fund returns and calculated their mean, standard deviation, and skew (see Exhibit 2). The study compared the fund returns data distribution with a hypothetical normal curve constructed with the same mean and standard deviation. Again, we considered the large-cap category and mid-/small-cap category for this analysis.

- Large-Cap Category: We witnessed a positive skew (skewed to the right), which implies that, generally speaking, the mean was higher than median, indicating that few funds generated extraordinary returns, pulling the category average higher whereas the performance of most funds lies to the left of the mean.

- Mid-/Small-Cap Category: We noticed a negative skew (skewed to the left). This implies that the mean was less than the median, which means that only a few funds with large underperformance were dragging the mean down, but that most funds generated superior funds in this category.

This analysis indicates that, at least in the large-cap category, the majority of the funds failed to beat the category average.

What is more challenging is that the relative peer performance of a mutual fund has not been consistent (see Exhibit 3), which means that funds that have outperformed in one period failed to maintain their superior performance in the following periods. In Exhibit 3, funds were classified into four quartiles based on their performance over the five-year period between Dec. 31, 2008, and Dec. 31, 2013. The columns to the right showcase how many of the funds continued to outperform their peers over the period from Dec. 31, 2013, to Dec. 31, 2018. Some important inferences include the following.

- In the case of the large-cap fund category, only 14.8% of the 27 top-quartile funds continued to be in the top quartile the following five years. However, in the mid-/small-cap category, 42.9% of the 14 top-quartile funds continued to be in the top quartile in the following five years.

- The worst-performing funds have higher probability to continue their underperformance. For example, in the mid-/small-cap category, 35.7% of the 14 funds in the bottom quartile continued their underperformance and failed to break out from the bottom quartile.

- The highest number of fund mergers/liquidations was witnessed in the bottom quartile. For example, in the large-cap category, 35.7% of the 28 funds (i.e., 10 funds) in the bottom quartile failed to survive the period from 2013 to 2018.

The writing on the wall is clear. Fund outperformance is random and predicting an outperforming mutual fund may be as challenging as the stock-selection process. From a purely mathematical point of view, an investor has better odds of flipping a coin than identifying an outperforming active mutual fund. Therefore, investing via a systematic, style consistent, low-cost passive route could be a better bet for an investor.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

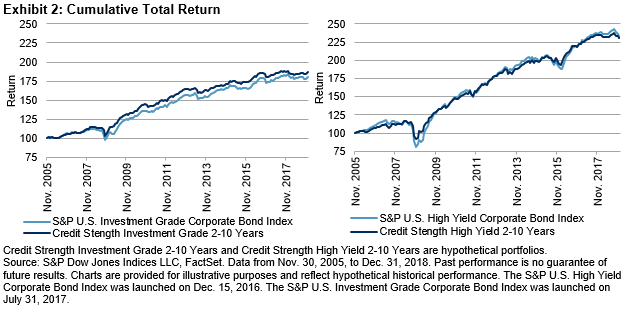

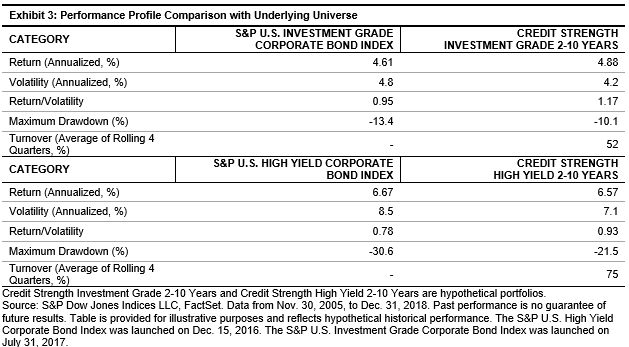

Exhibits 2 and 3 compare the back-tested performance of the credit strength portfolios with the underlying broad market indices. For investment-grade and high-yield bonds, credit strength portfolios reduced return volatility and improved risk-adjusted returns. The maximum drawdown was lower than the underlying universes during market downturns.

Exhibits 2 and 3 compare the back-tested performance of the credit strength portfolios with the underlying broad market indices. For investment-grade and high-yield bonds, credit strength portfolios reduced return volatility and improved risk-adjusted returns. The maximum drawdown was lower than the underlying universes during market downturns.

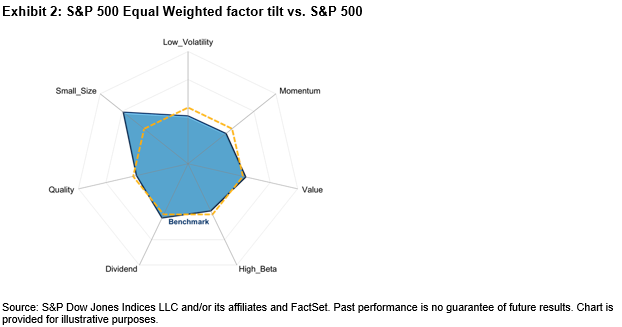

Equal Weight is a particularly good illustration of the small-size effect, since it holds the same stocks as the cap-weighted S&P 500. Exhibit 2’s factor exposure chart makes Equal Weight’s small cap tilt clear. Given

Equal Weight is a particularly good illustration of the small-size effect, since it holds the same stocks as the cap-weighted S&P 500. Exhibit 2’s factor exposure chart makes Equal Weight’s small cap tilt clear. Given