The Narendra Modi government will soon complete its five years in power. With polling underway to elect the next government, India is in election mode. Everyone is discussing politics and predicting the election results. The backers of the current government claim that the return of Modi will provide stability and ensure development. On the other hand, those backing the opposition, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance, claim that a change in government is required in order to maintain secular harmony in the country. Neither side would welcome a hung parliament.

Over the past five years, the government made several landmark policy decisions and initiatives like the Goods and Services Tax (GST), demonetization, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, and Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, among others. Many of the reforms have had a major impact on the Indian economy. Even after disruptive reforms like the demonetization and GST, economic growth is back on track. Opinion surveys conducted before the polling suggest a close fight and the current government may not achieve the majority it got last time. The outcome is anyone’s guess until the counting begins on May 23, 2019.

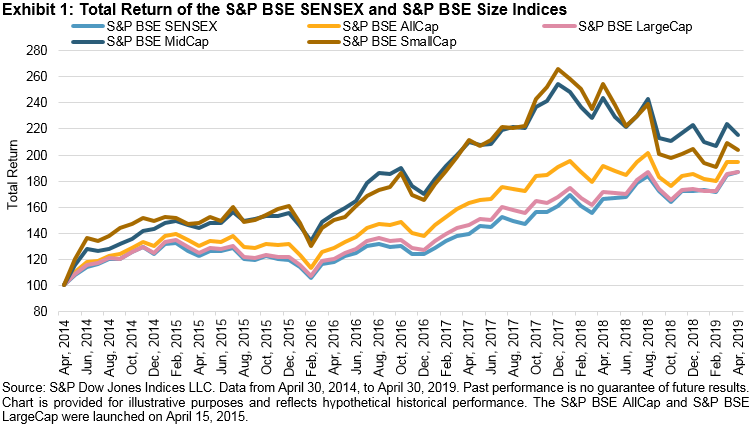

The S&P BSE SENSEX TR moved from 30,242.22 on April 30, 2014, to 56,443.02 on April 30, 2019—a five-year absolute return of 86.64%. The S&P BSE AllCap, a broad benchmark index with over 1,000 constituents, had a five-year absolute return of 94.49%. Among the size indices, the five-year absolute return of the S&P BSE MidCap was the highest, at 115.35%, followed by the S&P BSE SmallCap, at 103.98%, while the S&P BSE LargeCap was at 86.70%. Exhibit 1 depicts the total returns of the S&P BSE SENSEX, S&P BSE AllCap, S&P BSE LargeCap, S&P BSE MidCap, and S&P BSE SmallCap for the five-year period ending on April 30, 2019. The capital markets in India have presented significant returns to investors in the past five years.

Exhibit 2 provides the five-year absolute returns of the S&P BSE AllCap Series. Among the sub-sector indices in the S&P BSE AllCap, the S&P BSE Finance and the S&P BSE Energy posted the best five-year absolute returns of 133.40% and 130.81%, respectively, while the S&P BSE Telecom had the worst return, at -15.92%.

Exhibit 2 provides the five-year absolute returns of the S&P BSE AllCap Series. Among the sub-sector indices in the S&P BSE AllCap, the S&P BSE Finance and the S&P BSE Energy posted the best five-year absolute returns of 133.40% and 130.81%, respectively, while the S&P BSE Telecom had the worst return, at -15.92%.

| Exhibit 2: Five-Year Absolute Returns of the S&P BSE AllCap Index Series | |||

| INDEX | INDEX VALUE ON APRIL 30, 2014 | INDEX VALUE ON APRIL 31, 2019 | 5-YEAR ABSOLUTE RETURN (%) |

| S&P BSE AllCap | 5,213.46 | 2,680.53 | 94.49 |

| S&P BSE LargeCap | 5,428.59 | 2,907.61 | 86.70 |

| S&P BSE MidCap | 17,658.53 | 8,199.81 | 115.35 |

| S&P BSE SmallCap | 17,196.43 | 8,430.31 | 103.98 |

| S&P BSE Finance | 7,550.88 | 3,235.19 | 133.40 |

| S&P BSE Energy | 6,486.04 | 2,810.11 | 130.81 |

| S&P BSE Consumer Discretionary Goods & Services | 4,187.02 | 1,952.72 | 114.42 |

| S&P BSE Information Technology | 20,380.90 | 9,899.00 | 105.89 |

| S&P BSE Basic Materials | 3,642.73 | 1,889.44 | 92.79 |

| S&P BSE Fast Moving Consumer Goods | 14,825.49 | 7,937.85 | 86.77 |

| S&P BSE Utilities | 2,411.91 | 1,572.64 | 53.37 |

| S&P BSE Industrials | 3,555.84 | 2,456.68 | 44.74 |

| S&P BSE Healthcare | 15,934.28 | 11,615.71 | 37.18 |

| S&P BSE Telecom | 1,065.96 | 1,267.81 | -15.92 |

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Data from April 30, 2014, to April 30, 2019. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Table is provided for illustrative purposes and reflects hypothetical historical performance. The S&P BSE AllCap, S&P BSE LargeCap, S&P BSE Finance, S&P BSE Energy, S&P BSE Consumer Discretionary Goods & Services, S&P BSE Basic Materials, S&P BSE Utilities, S&P BSE Industrials, and S&P BSE Telecom were launched on April 15, 2015.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source: “

Source: “