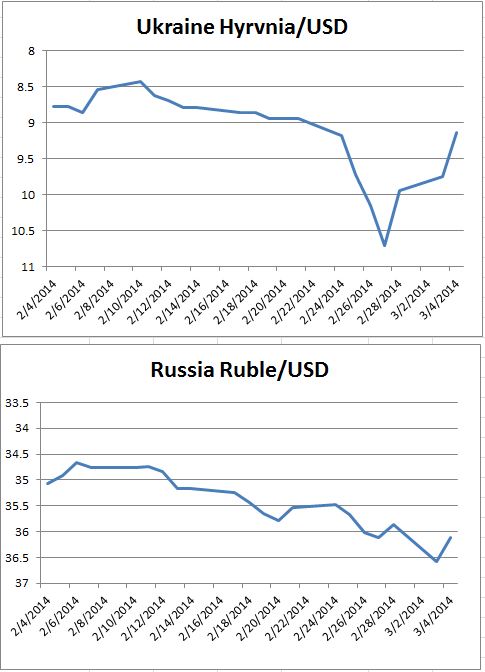

Russia and the Ukraine are dominating trading around the world since last Friday. The charts show the losses and rebound in the stock markets and currencies in the Ukraine and Russia. The bounce back reflects both a seemingly more moderate comment from Russian President Putin on Tuesday morning as well as the markets pausing after a plunge.

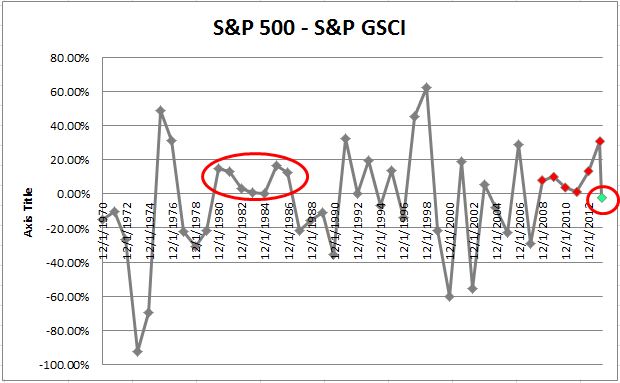

At times the political risks far out-weigh any economic concerns. Moreover, the reaction to Russian troops in the Crimea wasn’t limited to markets in Kiev or Moscow. The US stock market dropped and global oil prices rose. One of the largest jumps was wheat. Looking forward, if the dust settles and the Ukraine remains an independent nation, the stock markets and the currencies are likely to recover. The turn will come once there is good reason to believe the political situation will return to its pre-crisis position – so there may be a buying opportunity. However, there are several possible negative scenarios. The crisis could become a stalemate in which both the Ukrainian and Russian stock markets would probably drift downward, currencies would not rebound and both countries would face recessions. Any economic sanctions imposed by the US or the EU would hasten both recession and further currency weakness in Russia while having only limited benefits for the Ukraine. If Russia were to assume effective control of the country, the disappearance of Ukraine’s stock market cannot be ruled out. In some crises markets collapse. In others, including in wars, markets vanish.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.