Most stock indices where the weight of each stock depends on its market value are “float adjusted” meaning that the index only counts those shares that are available to investors and excludes closely held shares or shares held by governments or other companies.

The S&P 500 moved to float adjustment in in 2004-2005. Initially many investors expected substantial changes would result. By most estimates, between 10% and 15% of the stock of each company in the index is held by ETFs or indexed money managed for pensions, endowments or mutual funds. With a block that large held by index trackers, it would seem that counting only the stock that is readily available to investors and index trackers would matter. There were two counter arguments raised by some analysts. First, the stocks in the S&P 500 are all liquid. Currently a stock should exhibit at least 100% share turnover in a year when it joins the index; most companies in the index surpass this by a wide margin. Second, the index has a long-standing requirement that at least 50% of a company’s outstanding stock be part of the public float when it entered the index so low-float companies were excluded.

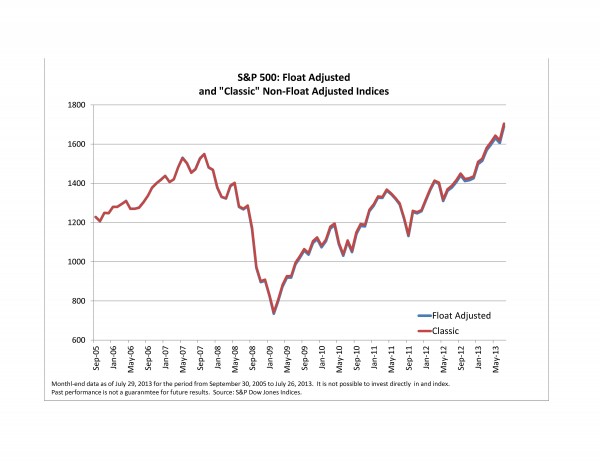

Looking back to September 2005, when the index became float adjusted, we can see the results of float adjustment. The chart shows the official or float adjusted S&P 500 and the same index without float adjustment. (S&P Dow Jones Indices calculates both versions.) In terms of price performance, the difference is very small – barely visible on the chart. The difference in index levels on July 26, 2013 – almost eight years since the introduction of float adjustment– is 13 index points or 77 basis points. The weight of the ten largest stocks in the float adjusted S&P 500 as of July 26th close is 18.09%, slightly less than the ten largest stocks in the non-adjusted index which were 18.14%. One of the ten largest stocks in the non float-adjusted index, Wal-Mart, does not make it to the top ten in the float adjusted index because closely held shares are excluded.

Does all this mean that float adjustment was unnecessary? No. Rather the average float factor – the percentage of shares in public float – across all 500 stocks in the index today is over 97%. In the U.S. large cap market segment that the S&P 500 tracks, the vast majority of stock is not closely held. Compare the 97% to the same statistic for the S&P Small Cap 600, 91% or the S&P Europe 350 at 82%.

Details on float adjustment are available on the S&P Dow Jones Indices web site,

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.