The S&P 500 Low Volatility Index® made a valiant comeback in late 2018 after trailing for most of the year. The strategy index finished the year well by just staying in positive territory at a 0.27% gain, when the broader S&P 500 declined 4%. It was also the best performing factor index among those based on the S&P 500. To date in 2019, it is predictably trailing the broader benchmark, up 9.2% versus a gain of 10.1% for the S&P 500.

Since the last rebalance for the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index, volatility continued to increase universally across all sectors of the S&P 500. Among the sectors that increased the most in volatility was Information Technology, up five percentage points, while Utilities’ volatility increased the least.

It is therefore not surprising that the low volatility index increased its weight in Utilities in the latest allocation shuffle; the sector now composes a quarter of the index. The other significant shift was Health Care, which gave back what it gained in allocation in the previous rebalance. Unexpectedly, Information Technology’s weight in the low volatility index remained more or less unchanged. This likely means that volatility levels of stocks within the sector were widely dispersed, with pockets of relative stability.

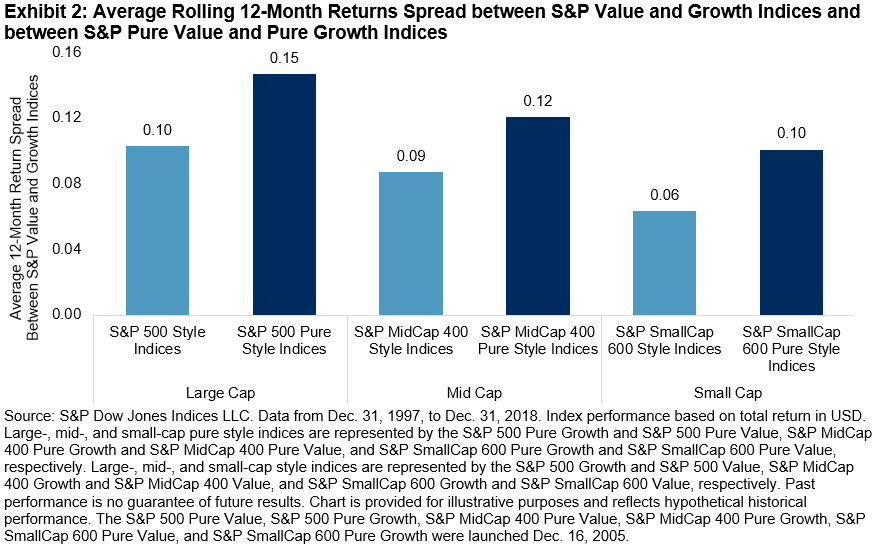

The relative performance of value and growth indices moves in cycles over time, thus market participants could potentially make tactical adjustments to take advantage of short-term deviations in relative value. Exhibit 2 illustrates the style return spread (value minus growth) for the large-cap, mid-cap, and small-cap style and pure style indices.

The relative performance of value and growth indices moves in cycles over time, thus market participants could potentially make tactical adjustments to take advantage of short-term deviations in relative value. Exhibit 2 illustrates the style return spread (value minus growth) for the large-cap, mid-cap, and small-cap style and pure style indices.