The S&P Style Indices and the S&P Pure Style Indices have distinct long-term performance differences and risk/return characteristics. We highlighted those in a prior blog where we reviewed the two approaches to constructing traditional style and pure style indices.

What are the drivers of the return differentials between pure style and style? We know that pure style indices differ from style indices in two aspects: weighting scheme and security selection. In this post, we continue to take a deeper dive into these style indices by examining the impact that weighting scheme and style selection have on relative performance.

To estimate the portion of excess returns arising from weighting scheme,[i] we compute the hypothetical market cap weighting of the pure style indices. We then compare the returns of the market-cap-weighted versions to the returns of the actual indices, which are weighted by style score.

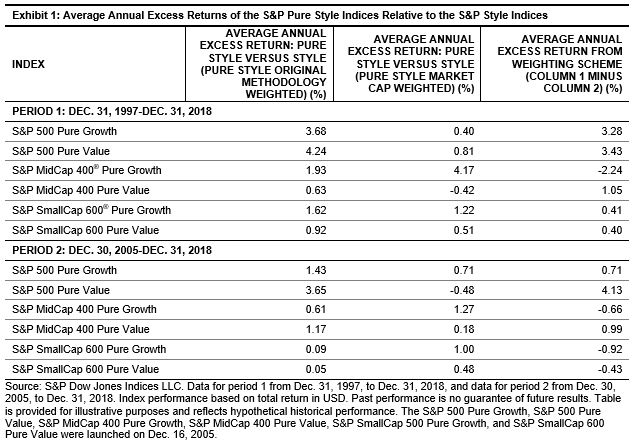

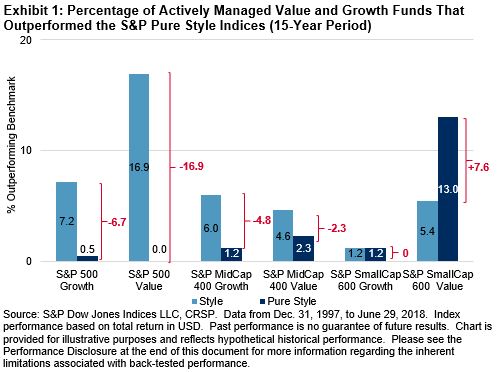

Exhibit 1 shows the average annual excess returns of the pure style indices relative to the style indices. The second column shows the average annual excess returns when the pure style indices are weighted by market cap. The difference between the first and the second column is an approximation of the resulting excess returns coming from alternatively weighting. For example, the average annual excess return of the S&P 500® Pure Growth and S&P 500 Growth in period 1 was 3.68%, of which roughly 3.28% was due to the weighting scheme.

Over the long-term investment horizon, with the lone exception of the S&P MidCap 400 Pure Growth, weighting by style score resulted in positive excess returns compared with weighting by market cap.

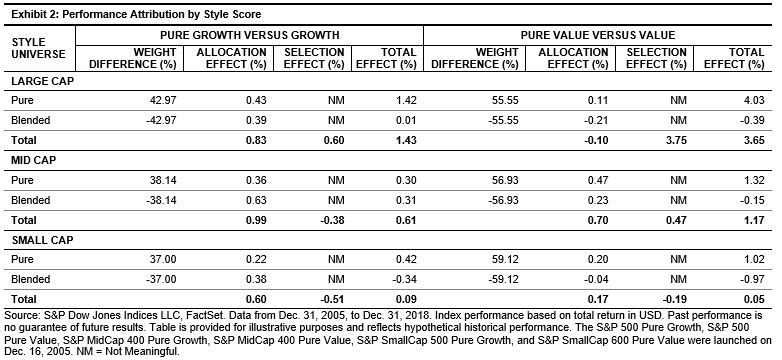

Next, we determine the performance impact of holding only pure style securities—those with a style score of 1—compared with the overall style universe, which contains pure and non-pure securities. To test this, we group securities of a given style universe into two groups (pure and blended) and look at the performance attribution using the groupings.

The allocation effect in Exhibit 2 indicates the amount of average annual excess returns that were attributable to style purity between the S&P Style Indices and S&P Pure Style Indices.[ii]

For the most part, the difference in style purity (pure versus blended), as indicated by allocation effect, contributed positively to excess returns, with the exception of the S&P 500 Pure Value. For example, the average annual excess return of the S&P 500 Pure Growth over the S&P 500 Growth over the entire period was 1.43%, of which the difference in value definitions (allocation effect) added 0.83%.

In an upcoming post, we will review allocation differences among sectors for the two style series to see if stock selection remains the main driver of the performance differential.

[i] It is not possible to cleanly attribute how much of the return difference came from security selection versus weighting by style score. This is because style scores are used in both selection and weighting, creating an interaction effect between the two.

[ii] Although reported in Exhibit 1, selection effect is not meaningful for this analysis, as it also includes the interaction effect between selection and weighting. Exhibit 2 better represents the impact of the weighting scheme on performance.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices’ “

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices’ “