Sovereign bonds remain largely unanalyzed by investors from a carbon risk and reporting perspective. This is despite clear acknowledgement in the Paris Agreement that governments have a critical role in curtailing global warming,[1] and the Financial Stability Board’s warning that climate change could affect all asset classes and the stability of the broader financial system.[2]

A key obstacle has been defining the appropriate metrics. As sovereign bonds provide capital to national governments, it is a government’s carbon emissions that we are focused on, but opinions vary on the appropriate breadth of ownership and responsibility.

- Are a government’s emissions just those produced directly through their expenditures, or should they also include those of the nation’s people and private companies?

- What about the emissions embedded within goods produced domestically then shipped overseas or imported goods consumed in the country?

- Is risk greater if a country consumes more emissions than it produces, if it has more emissions per capita, or if its level of debt is high relative to its emissions?

There is no right or wrong answer, but the choice of metric produces different insights.

Taking a Narrow View

A government’s emissions are those generated from its provision of public services. This limits double counting so it is neat from a carbon accounting perspective, but it is open to criticism for underrepresenting the emissions sovereign debt finances and the role of governments as regulators. The ability of a government to raise capital at competitive rates is based on the strength of the whole economy, not just the public sector. Similarly, the financial impacts of climate change will not be limited to the public sector, and the resilience of the economy will be affected by the influence a government exerts over private markets via regulation and taxation. Carbon taxes and renewable energy subsidies are good examples of the regulatory reach a government can exercise to influence production and consumption patterns of private firms and individuals. A broader approach counts all emissions produced within a country’s territorial boundary so the entire economy becomes the unit of analysis, but this method is exposed to double counting.

Accounting for Carbon in Imports and Exports

Governments generally report emissions produced within their borders, but this means that carbon can essentially be exported. Emissions tend to be exported from high-emitting industries in highly regulated countries to those with less stringent regulation. A carbon “balance of trade” approach helps address the demand side of the equation, and it is notable that net consumers are typically developed economies that typically outsource most production emissions to emerging economies.

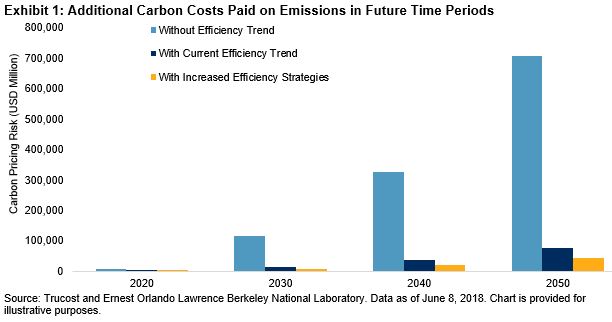

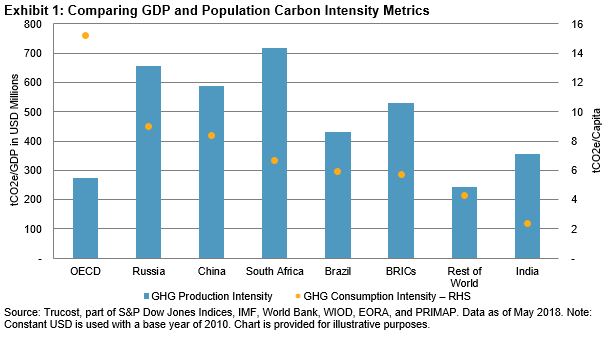

To compare countries with economies of different size, we need to create a carbon intensity metric. Normalizing emissions by the level of government debt is one approach, but results are skewed by the different debt levels of countries that may disguise more environmentally relevant production and consumption patterns. An alternative is to express the carbon intensity relative to GDP. This is particularly appropriate if using a production-based approach to quantify a country’s carbon emissions because the territorial boundary mirrors the scope of GDP calculations. To take account of consumption, a per capita denominator provides a different perspective. However, the metrics can produce significantly different insights. As Exhibit 1 highlights, when using GDP-based intensities, OECD countries appear to be among the most carbon efficient in the world, but when using emissions per capita, they are the worst. The opposite is true for most BRIC countries. This illustrates the exportation of emissions from developed to emerging economies, which is not visible in the GDP-based metrics.

So we see that the choice of metric produces different insights and implied actions—the key is understanding when to apply which metric.

To explore in further detail, read Accounting for Carbon: Sovereign Bonds.

[1] https://unfccc.int/process/the-paris-agreement/status-of-ratification

[2] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/about/

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.