Water scarcity risk has been in the spotlight recently with Cape Town’s efforts to avert “Day Zero” and the risk of taps running dry. Although this risk appears to be receding through radical conservation measures, including wholesale elimination of abstraction rights in some cases, it underlines the common global challenge of increasing fresh water scarcity.

From a business perspective, examples such as Cape Town illustrate that water is shifting from an operational concern of securing day-to-day supplies for production sites, to a wider strategic concern for companies. For example, the 2017 CDP Water Survey found that 70% of respondent companies were now disclosing water targets to their board, and they committed to a new investment of USD 23 billion in water projects in 2017.

Nonetheless, Trucost data indicates that most companies have substantial exposure to water risk in their supply chains that is unmeasured and unreported. For a typical company, as much as two-thirds of water-related impacts occur within the supply chain. In some cases, this can be even more pronounced—Nissan Motor’s supplier engagement in 2017 uncovered supply chain water consumption 20 times that of its direct operations.[1]

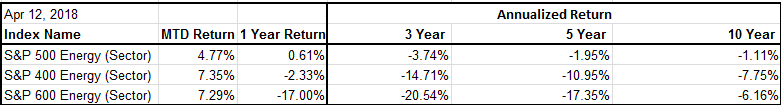

Where these water risks aren’t adequately measured, they represent substantial “unpriced risk” to companies, with global-listed companies having undisclosed water risks totalling USD 555 billion.[2] When the full costs of water scarcity and pollution are accounted for, this represents a substantial share of average profit at risk across a number of sectors (see Exhibit 1).

While companies have relied upon historical data when assessing the exposure of their supply chain to water risk, this may be a poor indicator of future risk associated with climate change and rising water scarcity. Recommendations by the G20 Taskforce on Climate Related Financial Disclosure[3] emphasize the need for companies to gather forward-looking data and explore the extent to which their business model and profitability is at risk under different climate change and water scarcity scenarios. Water is a crucial element of climate risk, with current projections pointing to a 40% gap in available supply of fresh water to demand by 2030.[4]

As a response to these risks, companies should understand how their business strategy and growth depend on water. Trucost has worked with business leaders like Ecolab to create industry-leading approaches to value water risks, set context-based water targets, and measure their maturity on important factors like governance, water measurement, target setting, and water stewardship. We’ve recently supported Braskem in setting long-term, basin-level water reduction targets that account for changes in local demand in line with rising scarcity, building on 2040 projections by the World Resources Institute.[5]

To manage water risk effectively, businesses need to consider water risks from every angle—looking back into their supply chain to identify hotspots of water risk and looking ahead to ensure their overall business model is resilient in the face of rising water scarcity.

[1] CDP (2017), A Turning Tide: Tracking corporate action on water security – CDP Global Water Report 2017.

[2] Trucost (2018)

[3] FSB (2017) Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures: Final TCFD Recommendations Report.

[4] McKinsey & Company (2009) Charting our Water Future: Economic frameworks to inform decision-making.

[5] World Resources Institute (2016) Aqueduct – Water Risk Atlas.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.