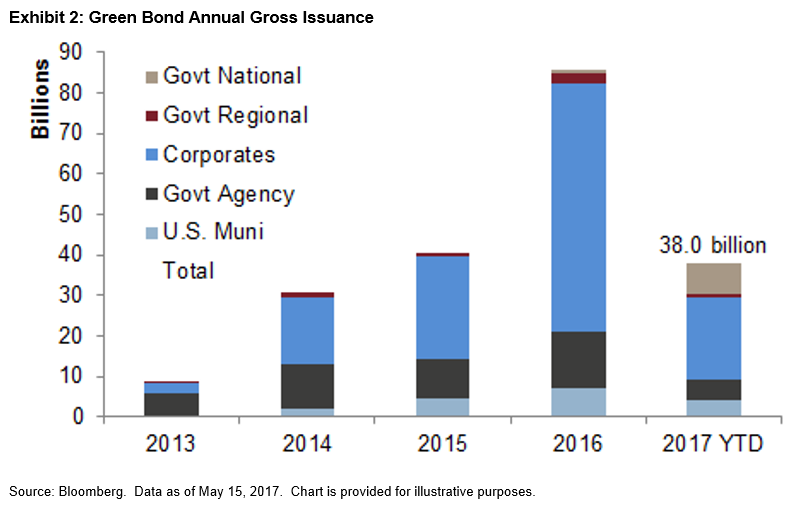

Green bond Issuance picked up in the first two weeks in May compared with the previous two-week period. Twenty new green labeled bond offerings were announced, including 11 U.S. municipal offerings with maturity structure (215 unique instruments). Issuance totaled USD 7.56 billion, of which USD 2.4 billion was in U.S. municipal bonds. Of note, German development bank KFW issued a medium term note (MTN) for EUR 2 billion (USD 2.2 billion) and Brazilian development bank (BNDS) issued a dual registered (144a and Reg-S) bond in the euro-dollar market worth USD 1 billion.

With the exception of January 2017, when France issued its first green treasury bond—which set a new record for size (USD 7.5 billion) in the green bond market—May 2017 is poised to set a new record for issuance.

Total issuance of bonds labeled as green in 2017 is nearing USD 38 billion and is positioned to surpass 2016 issuance, but the pace will need to accelerate for issuance to reach analyst expectations of USD 150 billion.

Related Indices:

Note that not all bonds listed above may be eligible for index inclusion. Please see the methodology documents for further details.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.