Should active managers shift away from well-diversified portfolios and concentrate only on “high conviction” holdings in hope of generating higher returns? We have suggested four consequences — higher risk, greater dominance of luck over skill, higher costs, and fewer outperforming funds — that are likely and logical outcomes of higher concentration. All four apply even for active managers with genuine stock selection skill. Once we consider the nature of skill, however, the case against greater concentration becomes even more compelling.

The argument for concentration relies on two assumptions: that manager skill exists, and that it is particularly acute at the extremes of conviction. Not only, e.g., must a manager be able to build a 100-stock portfolio that will outperform, he also must be able to identify which 20 stocks of the initial 100 are the best of the best. For concentration to work, both assumptions — that skill exists, and that it is acute at the extremes — must be true simultaneously. There is no evidence that either of them is. If it exists at all, the requisite skill must be quite rare. If this were not so, active funds would not be facing a performance challenge in the first place.

On the contrary, the evidence that manager skill is ephemeral is strong:

- The only source of excess return, or positive alpha, for the market’s winners is the negative alpha of the losers. In aggregate, professional active management is a zero-sum game.

- Because passive investors own a pro-rata slice of the market, their aggregate portfolio is identical to the aggregate portfolio of all active managers. But passive investment is intrinsically cheaper than active management, so that the average passively-managed dollar is arithmetically certain to outperform the average actively-managed dollar.

- In support of these conceptual points, the empirical evidence is unequivocal. Most active managers underperform benchmarks appropriate to their investment style, and the comparisons become more arduous as the timeframe for evaluation lengthens. Moreover, when above-average performance occurs, there is scant evidence that it persists.

Skillful managers sometimes underperform; unskilled managers sometimes outperform. The challenge for an asset owner is to distinguish genuine skill from good luck. The challenge for a manager with genuine skill is to demonstrate that skill to his clients. The challenge for a manager without genuine skill is to obscure his inadequacy. Concentrated portfolios will make the first two tasks harder and the third easier.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

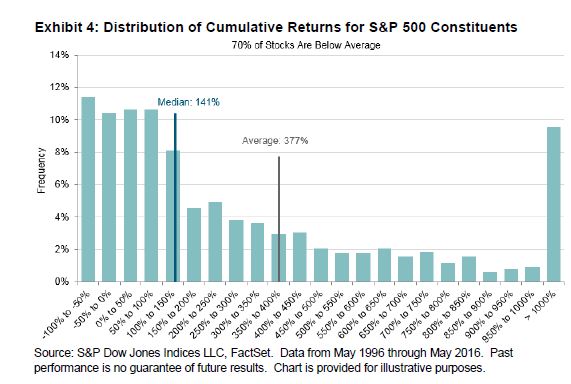

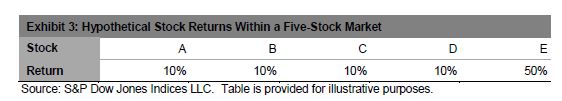

We can form portfolios of various sizes from these five stocks. There are five possible one-stock portfolios, four of which underperform the market as a whole. Alternatively, there are also five possible four-stock portfolios, four of which outperform the market as a whole. The expected return of the complete set of one-stock and four-stock portfolios is the same 18%, but the distribution of portfolio returns is different. In this case, holding more stocks increases the likelihood of outperformance.

We can form portfolios of various sizes from these five stocks. There are five possible one-stock portfolios, four of which underperform the market as a whole. Alternatively, there are also five possible four-stock portfolios, four of which outperform the market as a whole. The expected return of the complete set of one-stock and four-stock portfolios is the same 18%, but the distribution of portfolio returns is different. In this case, holding more stocks increases the likelihood of outperformance.