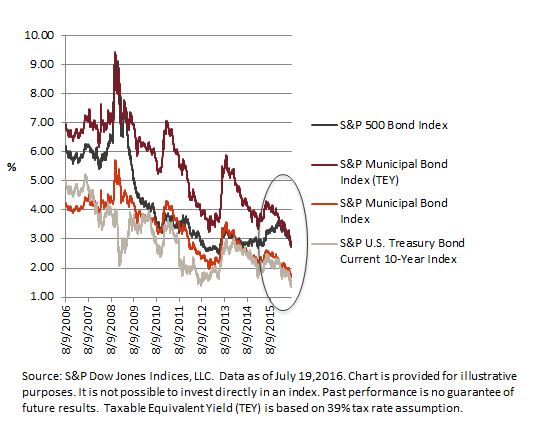

As we approach August, the U.S. bond markets have extended their malformed shape despite another round of chatter about the possibility of a Fed hike, this time towards year end. Subsequent to the June 2nd, 2016 blog Bond Market Malformation, Trouble Ahead? bond yields have compressed further.

Demand continues to outstrip the supply of U.S. investment grade corporate and municipal bond issues as investors seek incremental yield over Treasuries and safe harbors (risk off) during volatile periods. The result bond prices have continued to rise and yields have fallen.

- Record low municipal yields: The weighted average yield of bonds in the S&P Municipal Bond Index hit a low point not seen before in its 15 year life as the yield to worst (YTW) reached a low point on July 8th of 1.687%.

- The Taxable Equivalent Yield of the bonds in the S&P Municipal Bond Index is currently right on top of the yield of the corporate bonds in the S&P 500 Bond Index.

Chart 1: Select bond indices and yields (yield to worst):

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.