Between Christmas and New Year, the familiar roar of events turns staccato and the market is gently buffeted by meager trading volumes; the relentless pursuit of profit that agitates the flight of global capital is sedated. The books are largely closed; the offices of major financial institutions are staffed by fragile acolytes bereft of their titans. Decisions, if any, are postponed.

Considered contemplation (a luxury denied in more urgent times) is apt. What more appropriate position of comfort to consider the very nature of crisis?

Crisis, by our understanding of it, should be extraordinary, yet it seems crises are presented to the capital markets ordinarily. Why (and how) this happens is a deep question, involving not just market structure and probabilities but also human psychology. A simpler question is to ask what how we might comprehend the alarming frequency with which large movements occur in the equity markets: daily swings of over 10% in benchmarks like the S&P 500 are seven times larger than the average variation – theoretically they should be expected only once in billions of years.1 How then, can they occur so frequently?

The dynamics of volatility are the focus of our latest whitepaper, which explains how dispersion and correlation interact to create crises. One of the interesting features we examined was, in particular, how market volatility reacts to high correlations, and what happens if dispersion moves subsequently. The concepts are fairly simply expressed, and the viewpoint can provide a useful insight into the nature of crisis.

Correlations drive market risk

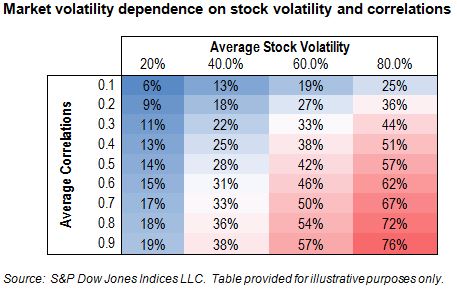

“The market” is made up of a large number of stocks. Each has its own volatility (which may vary) and each stock correlates to some degree (which may vary) with every other stock in the market. All else being equal, market volatility will be higher if the volatility of the average stock rises and if the average stock-to-stock correlation rises. The precise relationship can be derived analytically; the table below illustrates the range of market volatility that can result from a reasonable (and historically realistic) range of input variables.

A very wide range of market volatilities is possible and, viewed from this perspective, the importance of correlations is starkly apparent. In fact, comparing the top left of the table to the bottom right, it seems quite feasible that from one environment to another market volatility might increase by a multiple of over twelve times. An event that a risk manager might previously dismiss as impossible “because it is twelve standard deviations away from the mean” can suddenly become simply “standard.”

At high correlations, molehills become mountains.

Correlations also help to explain the “flashes” of volatility that occur from time to time. Stocks themselves encode the risk of the market they inhabit as well as whichever specific day-to-day or structural risks are particular to their business. The idiosyncratic, non-market risk of each individual stock is clearly particular to that stock. However, the aggregate level of all such risks among all the stocks in the market is no doubt of interest to risk managers, and in fact it is arguably an important characteristic of the market environment.

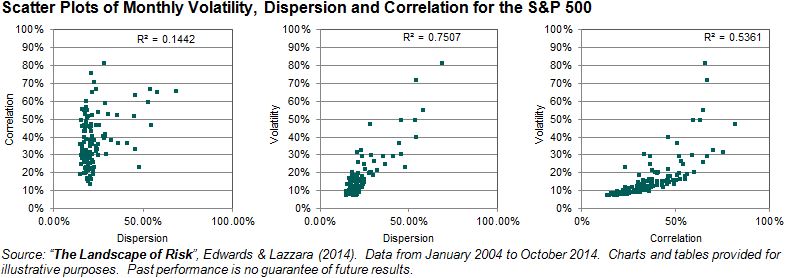

The idiosyncratic risks of every stock aggregate to a measure known as dispersion. Intuitively, one would expect dispersion move in the opposite direction to correlations over time, whereas (as per the table above) one expects market volatility to go up and down together with correlation. Here is a historical snapshot of each for an extended period in the S&P 500:

The fascinating, and important, observation to make from the scatter plots is that correlation and dispersion have been remarkably independent. This has a deeply important consequence. Other things equal, an increase of either correlation or dispersion will increase volatility. But at high correlation levels, any subsequent increase in dispersion will generally convert at an elevated multiple into market volatility. Since dispersion and correlations are somewhat independent, it is quite possible that, even during periods of high correlation, there will be small changes in dispersion – which entail far more dramatic effects in market volatility. And perhaps this explains why, as the “flash crashes” that followed the financial crisis demonstrated, in periods of high correlation, idiosyncratic events can have systemic consequences.

- Calculating such probabilities requires assumptions on how prices move – the most famous of which that price changes roughly follow a Normal (or “Gaussian”) distribution. This distribution is famous for good reason. It turns up all over the place; in fact the theory says that it should turn up most places, eventually. Beginning with Bachelier’s PhD thesis in 1900, through the Black-Scholes’s Nobel-prize winning options formula of 1973 and beyond to the present day, the normal distribution is inextricably linked with the mathematics of finance. Well, more fool us. “Incredibly unlikely” events happen all the time, it’s just that people can have short memories.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.