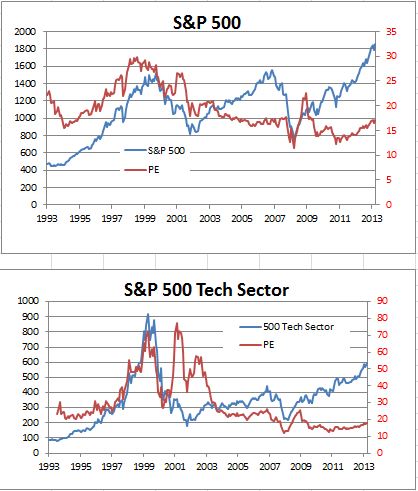

Whenever this bull market ends, it is likely to be with a bang, not a whimper. The bull market began on March 9th, 2009, five years ago. The last bull market lasted exactly five years from October 2002 to October 2007; the one before that – the great tech boom – lasted 10 years. This bull market isn’t that old. Aside from the passage of time, the next concern people raise is valuation – are stock prices “too high?” While valuations, measured by price-earnings ratios, are above long run averages, they are modest or almost reasonable compared to the technology boom of the 1990s. Moreover, the S&P 500 is not concentrated in a few stocks or one sector. Technology is closer to a fifth of the index value today than the third it was at the end of the 1990s. The index itself is not that concentrated either: the largest stock is less than 3% of the total market value.

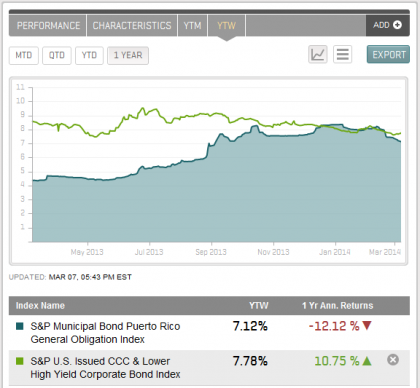

In keeping with the title, guessing the end of the bear market probably means guessing the next economic, political or financial upheaval. The situation in the Ukraine is not likely to end the bull market unless the US becomes involved in military action – an extremely remote possibility. A more likely scenario that might send the market lower would be large default of one or more junk bond issues. The long period of low interest rates has made people more adventurous with credit risk. Equity investors, especially after the bear markets in 2002 and 2007, should recognize that stocks can nose dive; bond investors would need memories extending back to the 1970s to understand some of the dangers. We seem to be nervously safe for the moment.

The charts show how the S&P 500, the Dow and the tech sector in the 500 have developed since 1993. The blue line is the index; the red is the PE ratio.